Microbiology

Microbiology

Producing next-gen polymers out of antimicrobial-resistant superbugs

Antimicrobial resistance is a survival strategy used by bacteria to disarm antimicrobials. In some cases, bacteria take advantage of proteins located on the surface of their body to pump out the molecules that would otherwise harm them. We discovered that a new family of these proteins can pump out polymer precursors. Therefore, they can be harnessed in the microbial production of such compounds.

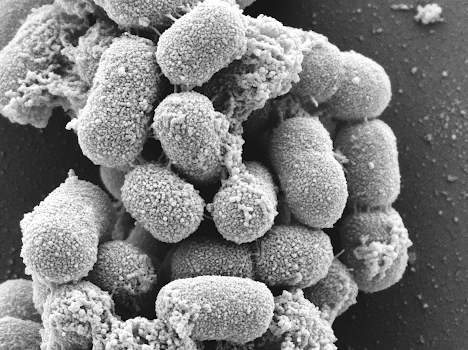

Bacteria survive in an array of environments, so they are constantly exposed to a wide variety of toxic molecules. To be able to survive in different environments, bacterial cells must be able to actively protect themselves from toxins. Often they do this by breaking down the toxins or by transporting them out of cells through proteins known as efflux pumps. Efflux pumps are molecular machines that sit on the surface of bacterial cells and pump toxins out. These pumps are found in all bacteria. They serve as an essential survival strategy for bacteria because they can recognize and pump out a wide range of molecules that differ in size, structure, and charge. Many efflux pumps are also associated with processes such as virulence, cell to cell communication, and antibiotic resistance.

Efflux pumps have been extensively studied for their role in antibiotic resistance and, as a result, are often referred to as multidrug efflux pumps. As the name indicates, these proteins contribute significantly to the development of resistance to drugs. In most cases, increased production of efflux pumps, results in resistance to multiple antimicrobials in bacteria giving rise to multidrug-resistant pathogens. The bacterial efflux systems are characterized into seven different families or superfamilies. Three of these families were discovered by members of our team in collaboration with other researchers. The proteobacterial antimicrobial compound efflux (PACE) family is the most recently characterized family by our laboratory.

The Acinetobacter chlorhexidine efflux (AceI) protein pump, was the first discovered member of the PACE family of efflux pumps. AceI was discovered in our laboratory while investigating how the pathogen Acinetobacter baumannii responds to chlorhexidine treatment. Chlorhexidine is an antiseptic that is used in hand washes, soaps, and disinfectants in the hospital. Many microbial pathogens, particularly those found to cause hospital-acquired infections, including A. baumannii, have, in recent years, gained a high level of tolerance to chlorhexidine. We found that AceI reduces susceptibility to chlorhexidine in A. baumannii by pumping chlorhexidine out of the bacterial cell.

Chlorhexidine is a synthetic biocide first manufactured in the 1950s. In contrast, AceI and other members of the PACE family are found in bacteria that diverged millions of years ago. Thus, these proteins have existed much longer on earth than chlorhexidine, which suggested to us that chlorhexidine is not the only target for AceI. This also indicated that AceI and other members of the PACE family must have important primordial roles other than conferring chlorhexidine resistance.

A family of linear, charged molecules known as polyamines share some chemical features with chlorhexidine. We, therefore, viewed them as potential substrates for AceI and other PACE members. Polyamines are widespread in nature. In some bacteria, they are essential for metabolism, motility, cell to cell communication, and growth. However, they can be toxic to cells when present at high concentrations. The most common biological polyamines include spermidine, spermine, cadaverine, and putrescine. The latter two are diamines, due to the presence of two amine groups at the end of the molecule. We found that expression of the aceI gene in A. baumannii was increased in the presence of diamines cadaverine and putrescine.

Further analysis demonstrated that AceI could protect the cell by pumping out toxic concentrations of diamines from the cell. In addition, we found that isolated AceI pumps can transport these compounds across a biological membrane. Therefore, it was concluded that diamines are substrates of the AceI pump and the likely primordial substrates.

Putrescine and cadaverine are being increasingly studied for industrial applications, especially in the production of bio-based polyamides (nylon) from renewable sources. At present, most nylon is synthesized from petroleum-based 1,6-diaminohexane. Petroleum is a limited resource, whose use has significant environmental consequences, which emphasizes the need to find renewable approaches for nylon replacement. Cadaverine (1,5 diaminopentane) is a highly promising candidate for bio-based nylon production. Cadaverine is currently synthesized through cadaverine-producing bacteria such as Corynebacterium glutamicum and Escherichia coli. However, one of the key limiting factors in the production of cadaverine on an industrial scale is its toxic effects on bacteria at high concentrations. This problem could be alleviated by using an efflux pump like AceI to pump cadaverine out of the cell, improving the yield and reducing the cost of production.

Original Article:

Hassan K, Naidu V, Edgerton J et al. Short-chain diamines are the physiological substrates of PACE family efflux pumps. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019;116(36):18015-18020.Next read: Genetics agrees: Africa is thriving in diversity by Neil Hanchard , Ananyo Choudhury , Zane Lombard

Edited by:

Massimo Caine , Founder and Director

We thought you might like

The struggle to comply with social distancing

Nov 24, 2020 in Psychology | 3 min read by Weizhen Xie , Stephen Campbell , Weiwei ZhangBronze Age food diversity: ceci n’est pas un bagel

Mar 30, 2020 in Evolution & Behaviour | 4 min read by Andreas G. HeissSurvival of the friendliest

Dec 13, 2017 in Evolution & Behaviour | 3.5 min read by Bridgett vonHoldt , Emily Shuldiner , Monique UdellMore from Microbiology

Monoclonal antibodies that are effective against all COVID-19 -related viruses

Jan 31, 2024 in Microbiology | 3.5 min read by Wan Ni ChiaPlagued for millennia: The complex transmission and ecology of prehistoric Yersinia pestis

Jul 31, 2023 in Microbiology | 3 min read by Aida Andrades Valtueña , Gunnar U. Neumann , Alexander HerbigHow cellular transport can be explained with a flip book

Jun 5, 2023 in Microbiology | 3 min read by Christina ElsnerThe Achilles’ heel of superbugs that survive salty dry conditions

Apr 24, 2023 in Microbiology | 4 min read by Heng Keat TamNew chemistry in unusual bacteria displays drug-like activity

Mar 21, 2023 in Microbiology | 3.5 min read by Grace Dekoker , Joshua BlodgettEditor's picks

Trending now

Popular topics