Antibodies, nature’s guided missiles, are designed to bind to their targets with high precision. The tighter they bind, the better they’re thought to perform. But what if we’ve been wrong all this time? Our research suggests that antibodies with a looser grip can sometimes be more effective. This unexpected finding could open new avenues for improved antibody-based therapies.

Our body is constantly guarded by our immune system, which defends us from external threats like viruses and bacteria, and even internal rogue cells that can become cancerous. Antibodies, which are special proteins in our bodies, play a key role in this defence. They work by recognizing and sticking to specific targets on viruses, bacteria or internal cells. In the field of immunological medicine, researchers have been developing antibody-based therapies to treat a wide range of diseases. For the past 20 years, the mantra among scientists has been: the tighter the binding, the better the result. Our research, however, points to a surprising observation – sometimes, antibodies that bind less tightly (lower affinity) may be more effective.

Traditional antibody-based treatments have focused on creating high-affinity antibodies to bind with a vice-like grip to targets on harmful pathogens or cancer cells. This strategy has proven its worth in countless medical scenarios, but when it comes to cancer, we asked ourselves: might there be a better way? In this context, as well as targeting the cancer cells for destruction by coating them with antibodies, we can also bind targets on immune cells with antibodies to stimulate their activity. Therefore, we asked whether stimulating our body's own immune cells, with a softer, looser touch, would be beneficial.

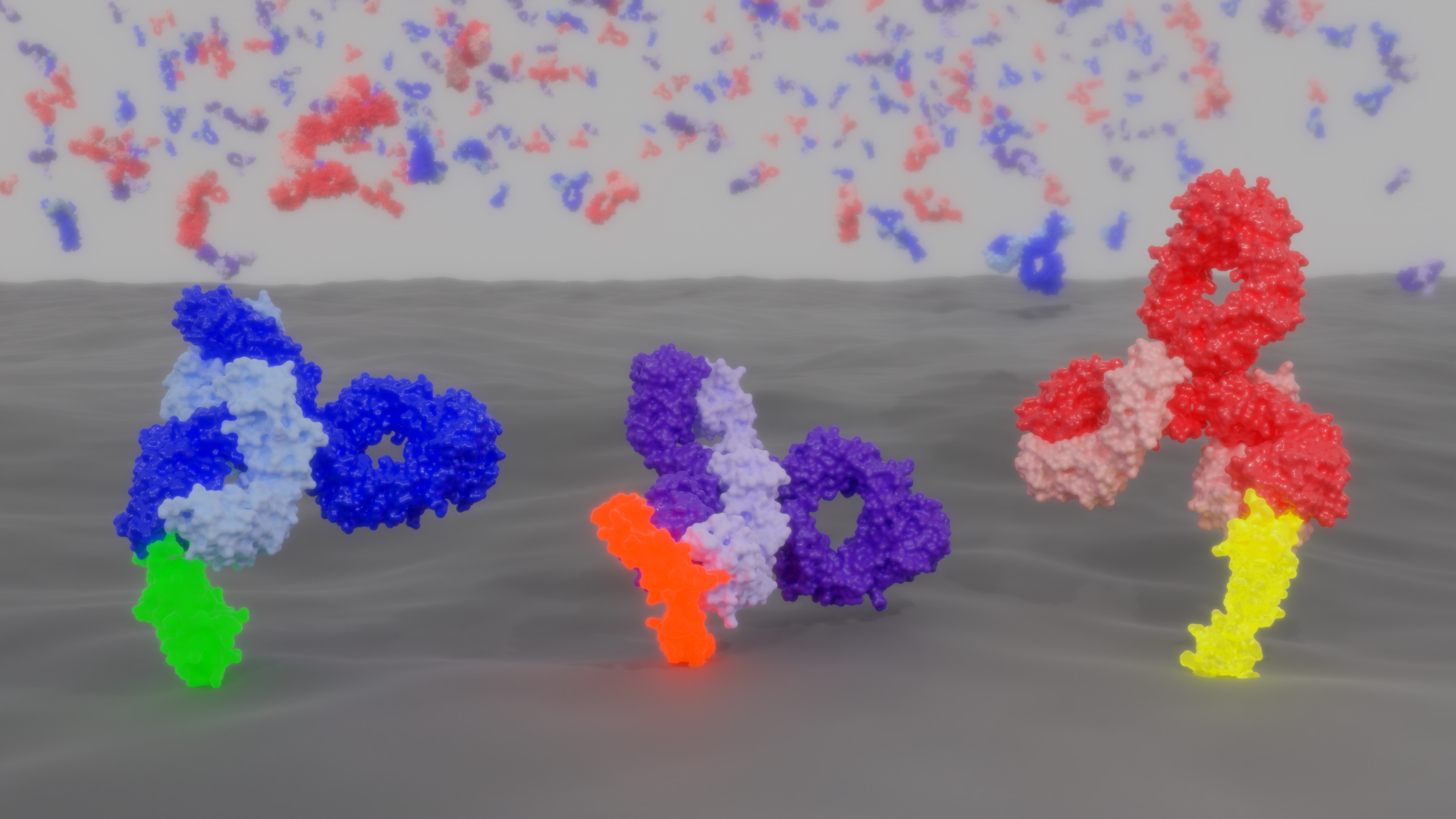

To address this, we ventured into uncharted territory, studying the relationship between binding tightness and immune response using antibodies directed against three different immune receptors, CD40, 4-1BB, and PD-1. Using detailed 3D models of antibodies, we subtly tweaked the parts of these antibodies that interact with the receptors, creating a suite of antibodies with varying binding affinities. Next, we evaluated the activity of these antibodies in cell assays and conducted in vivo experiments (inside living organisms) to observe their ability to stimulate immune cells to destroy tumours.

We found that the low affinity, looser binding antibodies were more active across all three receptors. As we gradually reduced binding strength, the activity of immune cells gradually increased, until we reached a point when the antibodies could no longer bind. In a surprising twist, reducing the binding strength of certain antibodies transformed them from being passive or even suppressive to actively promoting an immune response.

We also noticed that less tightly binding antibodies induced more target receptor clustering on the cell surface. These three immune receptors need to group together to become stimulated, which could explain why the immune cells became more active with the low affinity antibodies. The antibodies studied here targeted the two most prevalent classes of immune receptors (TNFR and IgSF) utilized in immunotherapy, indicating that these findings may be widely relevant to many other immune receptors.

This research shakes up the long-held belief that tighter binding antibodies are always better. Instead, our findings suggest that looser binding antibodies could offer greater activity for stimulating the immune system and developing more effective therapies, especially against cancer.

Our discovery also opens exciting new paths to better understand the complex inner workings of our immune system. As we delve deeper into this uncharted territory, we may uncover new strategies to control immune responses in different disease contexts, from autoimmune and infectious diseases in addition to cancer.

The revelation that less tightly binding antibodies can be more effective at stimulating the immune response has altered our understanding of the immune system and how to activate it. We now have a new approach for developing more effective, tailored antibodies for immunological medicine. As we move forward, it's crucial to further explore exactly how less tightly binding antibodies can stimulate immune responses so effectively, and whether this trait extends to all immune receptors. This knowledge will aid in creating therapies that fully harness the potential of low-affinity antibodies.

Original Article:

Yu, X., Orr, C.M., Chan, H.T.C. et al. Reducing affinity as a strategy to boost immunomodulatory antibody agonism. Nature 614, 539–547 (2023).

Health & Physiology

Health & Physiology